- Home

- Gurbaksh Chahal

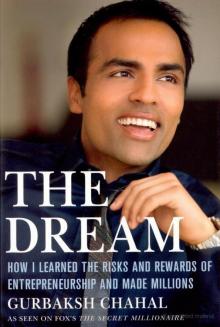

The Dream: How I Learned the Risks and Rewards of Entrepreneurship and Made Millions

The Dream: How I Learned the Risks and Rewards of Entrepreneurship and Made Millions Read online

The Dream

How I Learned the

Risks and Rewards

of Entrepreneurship

and Made Millions

Gurbaksh Chahal

THE DREAM

Copyright © Gurbaksh Chahal, 2008.

All rights reserved.

First published in 2008 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS.

Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world.

Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.

ISBN-13: 978-0-230-61095-8

ISBN-10: 0-230-61095-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chahal, Gurbaksh.

The dream : how I learned the risks and rewards of entrepreneurship and made millions / Gurbaksh Chahal.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-230-61095-8

ISBN-10: 0-230-61095-1

1. Success in business. 2. Entrepreneurship. 3. Internet advertising. 4. Market segmentation. I. Title.

HF5386.C466 2009

338’.04092—dc22

2008040123

A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.

Design by Letra Libre.

First edition: November 2008

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is for my father,

who taught me the importance of perseverance;

for my mother and grandmother,

who showed me the true meaning of love;

and for my three siblings,

who have been there for me every step of the way.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Prologue

1. An Immigrant Family

2. A New CEO

3. The First $40 Million

4. From Bollywood to BlueLithium

5. The Art of War

6. The Secret Millionaire

7. The Lessons of Entrepreneurship

Index

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank, first and foremost, my brother Taj, who was there when it all began; my sisters, Nirmal and Kamal, whose love and support have always meant the world to me; my agent, Mel Berger, my publisher, Airié Stuart, and my cowriter, Pablo Fenjves, who subjected me to the most humbling and best therapy session of my life; and of course God, for giving me the willpower to reach my dreams so early in life.

Prologue

When I was sixteen years old I started a company in my bedroom, and within a few months I knew exactly what I wanted to do with my life: I would become an entrepreneur. There was one thing standing in my way, however: school. If I was going to pursue my goal, I would have to do it full time, and I needed my father’s permission to drop out. This wasn’t going to be easy. More than a decade earlier, my family had come to America from India, settling in a one-bedroom apartment in a marginal section of San Jose, California. My father had arrived with $25 in his pocket, but his heart was full of dreams. “Education, education, education!” he would say, repeating it as if it were a mantra. “Education is the key that opens all the locks to all the doors in the world. My four children will become doctors and engineers. Maybe even both!”

I realized I couldn’t bear another day of school, and I was ready to take the biggest risk of my life. It was the defining moment that every entrepreneur eventually faces in one form or another. I had to have The Talk with my father. I was terrified about approaching him. He was a man who valued education above almost everything else. How could I tell him I wanted to drop out of high school? Then again, if I was to pursue my dreams, how could I not?

Finally, one night after dinner, I braced myself and plunged in. “Dad, there’s something we need to talk about,” I said. I had a hard time meeting his eyes, so I focused on his turban.

“What?” he snapped.

“You know that stuff I’ve been doing in my room?”

“No,” he said. “Not really.”

“Well, it’s turning out pretty well.”

“As long as it’s not interfering with school,” he said.

Man, was I in trouble. But I felt compelled to press on.

“Take a look at this,” I said.

Hesitantly I showed him my bank statement—the balance had edged north of $100,000. My father’s hand flew to his chest, like a man on the verge of a heart attack. “W-what is this? W-where did you get all this money?” He turned toward the kitchen and hollered for my mother. “Gurbaksh is going to jail!”

My mother came running from the kitchen, eyes wide with alarm. “What did you say? To jail? Who is going to jail?”

“No one is going to jail!” I said.

When they were somewhat calmer, I proceeded to explain how I’d spent the past six months studying the dot-com market, watching young companies grow very rich, very quickly, and trying to figure out how they did it. One of them, DoubleClick, had piqued my interest, primarily because it was among the first companies to put advertising on the World Wide Web. People were spending more and more time on the Internet and less time reading newspapers and magazines or parked in front of their television sets, and traditional advertising was rapidly losing ground. The Web was fast becoming the next big sales tool.

But my parents weren’t really listening. “I had hoped you would become a doctor,” my father said, looking at me balefully.

“Dad, this is better. I promise.”

Two days later, my father agreed to drive me to school to talk to the principal, and I was so grateful that I was near tears, but we Chahals are not emotional men, so I simply thanked him for believing in me.

“I believe in you because I can see you believe in yourself,” he said. “And obviously you’re doing something right.”

“I won’t let you down,” I said.

“You better not,” he said. “Because I’m giving you exactly one year to prove yourself.”

“One year?”

“Yes. One year. If this Internet business doesn’t work out, you’re going right back to school.”

When we reached the campus, we parked and I led my father to the principal’s office. He got to the point without wasting any time. “My son is dropping out,” he said.

“Why?”

“He has never liked school. He is going to do bigger things.”

By midsummer, after barely six months in business, I was posting revenues of $300,000 per month. And two years later, shortly after my eighteenth birthday—in what turned out to be one of the very first things I did as an adult—I sold my company for $40 million.

That was only the beginning.

1 An Immigrant Family

I was born in Tarn Taran, near Amritsar, in Punjab, India, on July 17, 1982, the youngest of four children, into a traditional Sikh family. My father studied hard and went to college, hoping to become an engineer, but when he graduated he couldn’t find a satisfying job and joined the police academy. He and my mother met in 1971, a match arranged by their families, and were married that same year. She was a nurse and enjoyed a modicum of independence, but

in most ways she was a traditional Indian woman. She had been taught that life revolves around the head of the household, the man, and she believed this to her core. When my father made a decision, she followed it without question. I would later find myself struck by this because her own family had actually pushed her to become independent, which in India—for people of a certain class—can only mean one of two careers: medicine or engineering. My mother wasn’t interested in engineering, and she didn’t think she had the patience or the stamina to become a doctor, so she settled for nursing, and she continued to work after she was married. In reality, though, after marriage her life was no longer her own. From that day forth, she did as she was told.

“It is the way it is,” my mother often said.

In 1973, a year after they were married, my parents had their first child, a daughter, Kamal. Two years later, they had another daughter, Nirmal. This was a blow. In India, families want sons. A son is a potential breadwinner. And a son carries the family name and legacy into the future.

At this point, my parents decided to put their future in God’s hands, and they both became exceedingly spiritual. They made frequent trips to the gurdwara, a Sikh temple, asking for a son, and they even prayed together at home.

Gurbaksh (left) in India with his grandmother and brother Taj.

Finally, late in 1978, my mother became pregnant again, and the following year they had a son, my brother, Taj. This was one of the greatest moments of their lives. God had listened to their prayers. They had a son! They were ecstatic.

Then they decided to try again. They thought the family would feel more balanced with two girls and two boys. They knew that perhaps they were being a little greedy, but the heart wants what it wants.

Again they went off to various gurdwaras to pray, and again they prayed at home. Again they gave God time to consider their request, and again their prayers were answered. When I came along in 1982, they named me Gurbaksh, which in Punjabi means “a gift from God.”

Gift or not, those were unstable times in India. On June 3, 1984, two years after I came along, a group of separatists, looking to create an autonomous Sikh state within India’s borders, demonstrated at the Golden Temple, the holiest of Sikh shrines. Indira Gandhi, the prime minister, ordered the army to clear the site, and there were many casualties—most of them Sikhs. To this day, the action is considered an unprecendented political disaster in modern Indian history.

My father had often talked about leaving India, and this incident convinced him that he should double his efforts. Like many Indians, he had his sights set on America, and he began to talk incessantly about leaving. There is no future for a Sikh in India, he would tell anyone who would listen. The country is corrupt. Opportunities are dwindling by the day. He wanted a better life, if not for himself then for his four children, and he believed that that life existed in America.

In 1984, my father applied for a visa through a U.S.- sponsored lottery system and received good news within months: The family’s papers had been reviewed, and they could emigrate to the United States as soon as they wished. (This was partly because my mother was a nurse; then and now, there was a shortage of nurses in the United States.) My parents were thrilled, of course. They would move to California, where they had a few friends, and they would send for us within a year. My grandmother would stay behind with my two sisters, my brother, and me.

After fifteen hours in the air, the plane landed in San Francisco and my parents were met by a friend at the airport. He drove them to his home in Yuba City, a farming community about 125 miles to the north. They could have taken jobs picking peaches, but since they were both educated people they held out for something more.

Not long after, they moved to San Jose, a bustling, melting pot of a city, and for the next few weeks, as they looked for an apartment of their own, they traveled from the home of one acquaintance to the next. They had arrived with only $25 dollars to their names, having left the bulk of their savings behind with my grandmother—to feed and care for us kids—so things were more than a little tight.

It turned into an especially difficult first year for my parents. My father had a tough time finding a job. As a Sikh, he wore a turban and a full beard, and—despite his flawless English—many westerners were put off by his appearance. Eventually, though, he found work as a security guard, for $3.35 an hour—the minimum wage at the time—and my mother found a job as a nurse’s aide (a step down from the work she had done in India, where she’d been director of nursing at a major city hospital). In due course they saved enough to make the deposit on a one-bedroom apartment on the gang-ridden east side of San Jose: first month, last month, and a security deposit.

In June 1986, my mother finally flew back to India to fetch us, and within days we were on our way to America: Kamal, Nirmal, Taj, my paternal grandmother, my mother, and me. I was a month shy of four at the time, so I don’t remember much about the trip or about that first year, but before long I began to adapt to life in the New World.

On weekday mornings, when my parents went off to work and the older kids left for school, I stayed behind with my grandmother, Surjit Kaur. Having spent much of her lifetime in the field, picking red peppers and chilies to support herself and her only son, a one-bedroom apartment in America was nothing to complain about—despite the fact that she was afraid to venture beyond the front door.

Every morning, after the house emptied out, she would park me in front of the TV, where I watched Barney and other similarly hypnotic shows. Then I’d wander into the kitchen to watch her cook—she prepared Indian food every day since it was all she knew—and before long my siblings would drift home from school, often in tears. My oldest sister, Kamal, had just turned thirteen, an awkward age under any circumstances, but particularly difficult for a recent immigrant. To the other kids, she and Nirmal were Fobs or Fobbies—Fresh Off the Boat—and they were ridiculed endlessly. My brother, Taj, was subjected to much of the same. A quiet, unobtrusive boy, he was not fond of attention, but it was hard to hide under the patka he’d been wearing since age five. “The other children call me towel-head,” he complained to my father.

“Don’t listen,” came the reply.

By the time I was sent to kindergarten, I had a vague idea of what I could expect, and I was terrified. Unfortunately, my fears were immediately confirmed. The class was full of Latinos, blacks, Asians, and a scattering of whites, but no Indians, so I was the one, true outsider. Turban-head! Conehead! Papa Smurf! And that was only the beginning.

“They call me Gandhi!” I told my father, wailing.

“So what? Gandhi was a great man. You should be proud.”

“Nobody wants to be my friend!”

“Why would you want to be friends with children who call you names? You don’t need such friends. You have your family.”

“I don’t want to go to school!”

“What? Not go to school! You are here to study, boy, and that’s what you will do! And I expect good grades from you—the best!”

“But—”

“That’s it! There will be no more talk on the subject.”

Two or three times a week, I’d come home with my turban in my hand, and my hair, uncut since birth, spilling onto my shoulders. My father told me to ignore the other kids, assuring me that it would stop, but he was wrong. The kids in my class were relentless.

My grandmother was never less than sympathetic, though. “Everything is going to be okay,” she would tell me. “Maybe things are a little bad now, but in my heart I know they will get better, especially for a smart boy like you.” That was enough for me. I believed her, and that gave me strength.

My father had no time for petty annoyances. On the contrary, he never tired of reminding us that we were a most fortunate family. Sometimes he went a little overboard. If it was a particularly nice day, for example, he might point it out. “How about this great weather?” he’d say. “In India, you go through nine months of heat and then two months of monsoon

s. But look at us. We live in California.”

And more: “Look how quickly things change in America! When I first got here, I was working as a security guard, but now I have a job with a company that manufactures hard drives for computers. People in this country are willing to take a chance on people like us.”

We shopped at the local Goodwill store, McFrugal’s, and at the Dollar Store, which was my favorite. Everything was a dollar. You could get shirts for a dollar. Shoes for a dollar. Three pairs of socks for a dollar. I actually looked forward to shopping there, because it was such a bargain. To this day, I like a good bargain. I learned at an early age that most people are very unwise about the way they spend their money, and I was determined not to be one of them.

I loved grocery shopping, too, because the stores were so colorful, and mostly because Mom always splurged on Twinkies. Shopping, for me, was almost a form of entertainment. I was out in the world, looking at stuff, seeing people, and I got a real kick out of using coupons to get good deals. I remember sitting at the kitchen table with my mother, helping clip coupons. We loved coupons, and I especially loved the ones for Little Caesars pizza. They would come with the mail every week or two, and I would look for them as if they were the prize in a box of Cracker Jack. For $5, you could get an extra-large pizza with two toppings, but the deal was only good on Mondays. So guess what we usually ate on Mondays? Two large pepperoni pizzas. That was some deal! Monday night became Family Pizza Night at the Chahals, and everyone loved it—even my grandmother.

“See how lucky you are?” my father would say. “Ordering in is a luxury.”

Gurbaksh at age seven with his sister Nirmal, at their apartment in San Jose.

We were poor, and my parents were struggling, but everything about America was already a dream come true.

Not for me though: On the first day of fourth grade, for example, I arrived at school in bright yellow slacks, a bright yellow shirt, and a matching yellow turban that my mother had made with her own hands. The children couldn’t stop staring, and even the teacher was curious. “Is it a special day for you people?” she asked.

The Dream: How I Learned the Risks and Rewards of Entrepreneurship and Made Millions

The Dream: How I Learned the Risks and Rewards of Entrepreneurship and Made Millions